Overview

Function factories are powerful tools for the R programmer. Without jumping through extra hoops though, they remove a fantastic feature of interactive work in R; evaluating a function’s name on its own (no () or arguments) will show the complete source code.

This post shows a way to use some of R’s metaprogamming to remove this problem.

Function Factories

As explained in Chapter 10 of Advanced R;

A function factory is a function that makes functions

Just as when you find yourself writing the same code over and over again you should consider making a function, when you find yourself making the same kinds of functions over and over again you should consider making a function factory.

When you know what to look for you see that they are quite common in R.

For example, the {scales} package contains loads of functions that make it easy to format {ggplot2} graph scales, but it can clearly be used elsewhere.

One of the functions is scales::comma_format().

This is a function that lets us design a new function that will take a numeric vector and apply certain formatting options:

library(scales)

whole_numbers <- comma_format(accuracy = 1)

nearest_100 <- comma_format(accuracy = 100)

european_style <- comma_format(big.mark = ".", decimal.mark = ",", accuracy = 0.01)Here we’ve defined three new functions, whole_numbers, nearest_100 and european_style all from a single function from {scales}: comma_format.

The name “function factory” is a good analogy: you can think of comma_format as a machine that builds you new functions based on a specification you provide.

And the results work nicely:

vec_of_nums <- c(0.4, 4523423.123, 1234.12)

whole_numbers(vec_of_nums)## [1] "0" "4,523,423" "1,234"nearest_100(vec_of_nums)## [1] "0" "4,523,400" "1,200"european_style(vec_of_nums)## [1] "0,40" "4.523.423,12" "1.234,12"Making your own Factories

It’s pretty easy to make your own function factory.

Recall that an R function will provide the last expression that is evaluated in the function body, if that expression is just a function definition (i.e. function() {}), then that’s what will be returned by the function.

For example, we will make a really basic function factory that will make functions that add to their input a certain amount:

adder <- function(x) {

function(n) {

n + x

}

}So the outer function that is bound to adder takes a value x and returns a new function that will add x to a provided input n:

add2 <- adder(2)

add100 <- adder(100)

add2(10)## [1] 12add100(10)## [1] 110X-ray vision on functions

One thing I love about R is being able to see the source code of any function I have loaded into a session.

For example, want to see the code for read.csv? Simply evaluate read.csv at the console:

read.csv## function (file, header = TRUE, sep = ",", quote = "\"", dec = ".",

## fill = TRUE, comment.char = "", ...)

## read.table(file = file, header = header, sep = sep, quote = quote,

## dec = dec, fill = fill, comment.char = comment.char, ...)

## <bytecode: 0x55a1bcb1f818>

## <environment: namespace:utils>From that, we can see that read.csv actually calls read.table with some pre-defined arguments.

But what do we get if we try that with the output from the functions we’ve received from the factory?

add100## function(n) {

## n + x

## }

## <bytecode: 0x55a1bb372148>

## <environment: 0x55a1bce97d90>We see that add100 takes an n, but the definition shown here doesn’t specify what x is.

If we didn’t know that add100 came from the adder function factory (and if we had named it less descriptively) we would have no idea what x is just from looking at the definition.

There is one simple thing we can do though: Every function carries a reference to it’s enclosing environment, so we can find out what x is like so:

environment(add100)$x## [1] 100But wouldn’t it be nicer to see that value of x when we evaluate add100 like any other function?

A quick family history

Development on R started in 1991 by Ross Ihaka and Robert Gentleman at the University of Auckland. R was based on S, originally made in 1976 by John Chambers at Bell Labs. The “S” came from Scheme, a dialect of Lisp.

Lisp has a reputation for being a weird old language that’s either not worth learning or will fundamentaly change the way you think about computers depending on who you talk to about it.

I quite like it, even though I’ve only scratched the surface of what it can do. I’m no expert but I do think it’s a very interesting language.

One thing Lisp is known for is its macro system. This is a powerful way to write code that writes other code. Lisp treats code and data in the same way so code is data; any operations you have that can manipulate data in lists can be used to manipulate code. You are writing code much closer to the abstract syntax tree than when you write in other languages.

Due to R having Scheme as a grandparent, it retains some of Scheme’s metaprogramming abilities, though they are a little watered down and certainly not as commonly used by the general R population. Nevertheless, anyone who has done an introductory R tutorial has relied on metaprogramming, e.g.

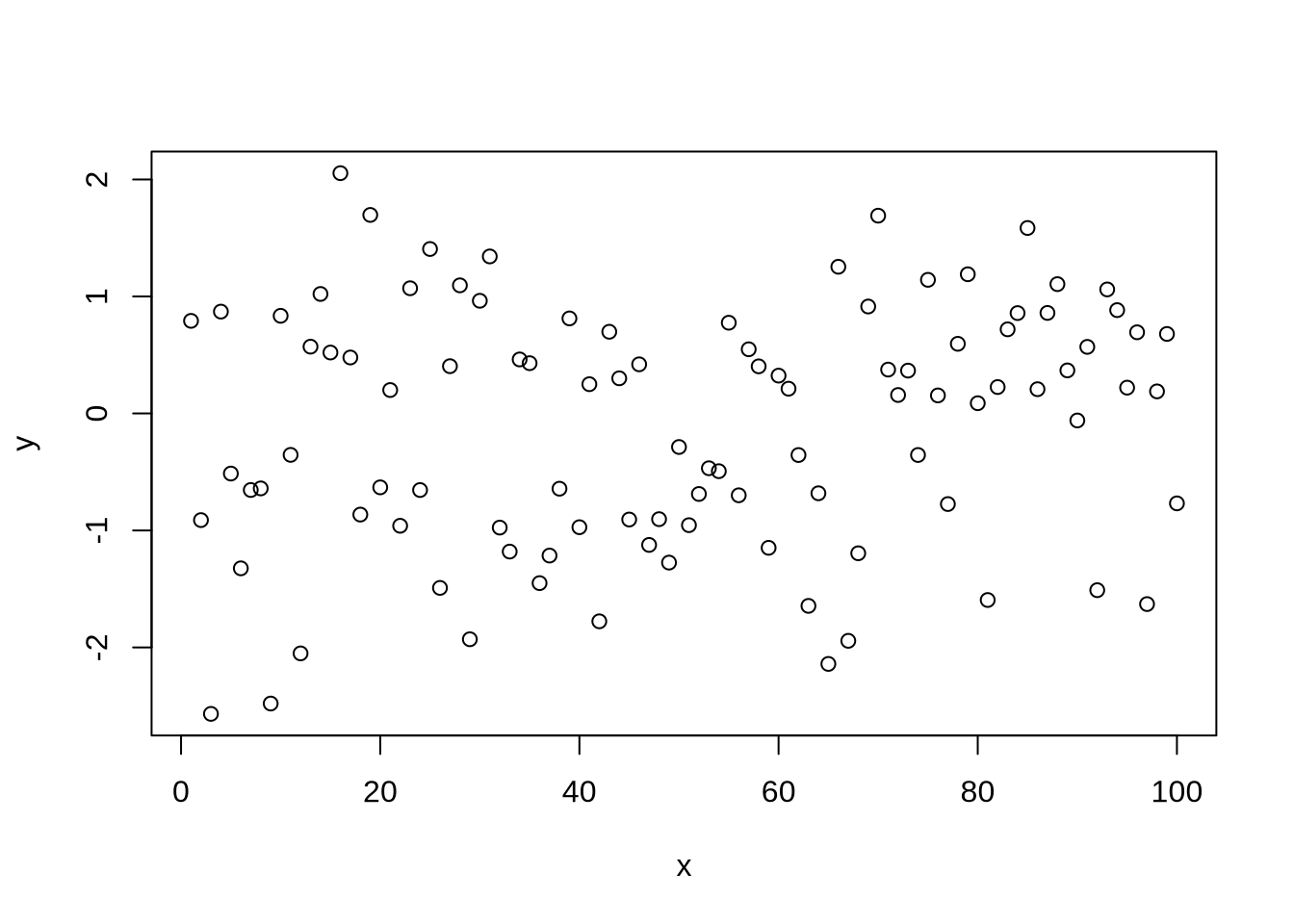

plot_data <- data.frame(x = 1:100, y = rnorm(100))

plot(y ~ x, data = plot_data)

How did R know what to label the plot axes by?

It was able to read the arguments passed in to plot, parse them out, convert them to characters and display them on the plot.

This reading and manipulating of code written by the user shows the potential for metaprogramming.

A Rough Guide to the Landscape

What follows isn’t a high quality map, it’s something I put together based on a few minutes of looking at the docs. It’s less a well-designed OS map and more a hastily scribbled hand map on the back of an envelope. Nevertheless, it shows the rough way that the different R classes for metaprogramming interact and the function that take you from one class to another:

For example, if we have a character string representing some code, e.g. "1 + 2", we can make this into a call object using str2lang, then evaluate this using eval to get 3:

my_code_string <- "1 + 2"

my_code_string## [1] "1 + 2"my_call <- str2lang(my_code_string)

my_call## 1 + 2eval(my_call)## [1] 3If I want to make a function that explains what it’s doing, I can do that with substitute, quote and deparse.

substitute and quote take us from R code into a call in slightly different ways and then deparse takes a call to a character:

very_clear_function <- function(x, y) {

x_sub <- substitute(x)

x_quo <- quote(x)

y_sub <- substitute(y)

y_quo <- quote(y)

cat(paste0(

deparse(x_quo), " = ", deparse(x_sub), " and ",

deparse(y_quo), " = ", deparse(y_sub), ", so ",

deparse(x_quo), " + ", deparse(y_quo), " = ", x + y

), "\n")

x + y

}

very_clear_function(1,2)## x = 1 and y = 2, so x + y = 3## [1] 3This function shows its working before providing the result.

We manipulated code to get calls and characters.

We can do the same to make the function factories clearer.

Transparent Factories

We are almost ready to improve the adder function to make it more transparent.

We need one final piece first though.

Lisp has an elegant way to quote code when making macros and evaluate portions of that code.

Lisp is something I’m going to talk at some point, but not today.

Instead we’ll just take as given the function bquote which is lisp-inspired without delving into why it’s called this or exactly how it works.

bquote does very similar work to quote, but allows us to signal to R that some items should be evaluated (in some environment) and then spliced back into the call.

For example

x <- 10

quote(x + 100)## x + 100bquote(x + 100)## x + 100bquote(.(x) + 100)## 10 + 100It is the .() bit that signals that x should be replaced with the actual value of x.

x will always need to be evaluated in some environment and we’ve just accepted the default which is the parent.frame.

This is the exact tool we need to make the function factory transparent.

We want to make a call that has the value of x evaluated and then build it back up to a normal function definition.

Our strategy is:

- Given some value of

x, we splice that into acallusingbquote(), evaluating it so it shows up not asxbut as the value ofxin the function factory environment (i.e. the value provided by the caller). - We then

deparseourcallin order to make it a list of strings representing the code. - We then take that vector and make it into an

expressionwhich is essentially a list ofcalls. - Then we can

evalit into a function definition:

And it’s a simple matter of arranging this all as function calls:

adder_transparent <- function(x) {

eval(

str2expression(

deparse(

bquote(

function (n) {

n + .(x)

}

))))

}Let’s have a look at the newer version of add100:

add100 <- adder_transparent(100)

add100(10)## [1] 110add100## function (n)

## {

## n + 100

## }

## <environment: 0x55a1bf1a72c8>There we have it, we can still get the value of x in the environment of add100 as we did before, but now we also have a transparent version of add100 that looks exactly as if we made a hand-crafted version:

hand_crafted_add100 <- function(n) {

n + 100

}

hand_crafted_add100## function(n) {

## n + 100

## }Conclusion

Even in languages that have metaprogramming as a key feature like Lisp and Julia, it’s common not to use it too much as it can be harder to reason about in some circumstances. R’s metaprogramming ability is far less advertised, so even more care should be used when writing code like this. It should be used only when it will add more clarity elsewhere in a project than the confusion it will bring right at its use-point.

In this example, I would only use it if there are strong requirements for someone to be able to look into the function definition and have all the code clear, for most function factories, I wouldn’t go to the effort.